Revamping pharma: Agile strategy shifts

The last decade, organizations are more and more confronted with different competitive pressures. Emerging technologies, rising consumer expectations, complex value chains and changes to the way people live and work are just a few factors that trigger organizations to rethink their strategy. Combined with a relatively poor track record on large scale change execution, this has created a need for organizations to reinvent their strategy definition and execution processes.

The global reach of pharmaceuticals and healthcare services companies (for convenience from here on ‘pharma’) adds another layer of complexity. Historically, pharma companies have allowed greater autonomy to the individual countries. In part, this is the result of a strong growth-through-acquisition strategy. But it is also by design: decentralization allows for a better understanding of local markets, including specific rules & regulations for commercial engagement. However, in recent years the downside of the model has also received much attention. As the need for innovation in all aspects of business increases – from R&D to marketing -, investments grow substantially. Smaller markets would not be able to keep up without the explicit support from global functions. This is true for complex drug development naturally, but equally so in digitaal technology. Such digital tech trends include the application of data-driven drug development, AI and Machine Learning, and an increasingly complex marketing tool stack to personalize the message to customers and patients. Consequently, pharma companies are increasingly centralizing their organizations. But as the level of centralization increases, so too the risk of increasing decision- making latency – the time it takes to reach a decision in response to a business change. Substantially hampering agility. Pharma companies need to face the challenge: how to align all the individual stakes and priorities of local and regional affiliates? Or put differently: how to leverage the benefits of scale that central organizations bring whilst avoiding the risk of inertia from being pulled in every direction?

This challenge is not new and pharma companies would do well to learn from companies that have taken on this challenge before. A large part of the answer is found in three plays: optimizing development speed, embracing agility across, and creating goal transparency and alignment. Only played out together they ensure the likes of Roche, Johnson & Johnson and Novartis can continue to be successful in their competition for market share and profit margins. We will examine these three plays up close with cases we guided to illustrate these.

Play 1: Optimize development speed

We would forgive you the first response of disappointment upon reading this statement. It is so obvious: how can organizations not pay attention to it? Unfortunately, even if they do pay attention to it, they only look at an individual element: IT.

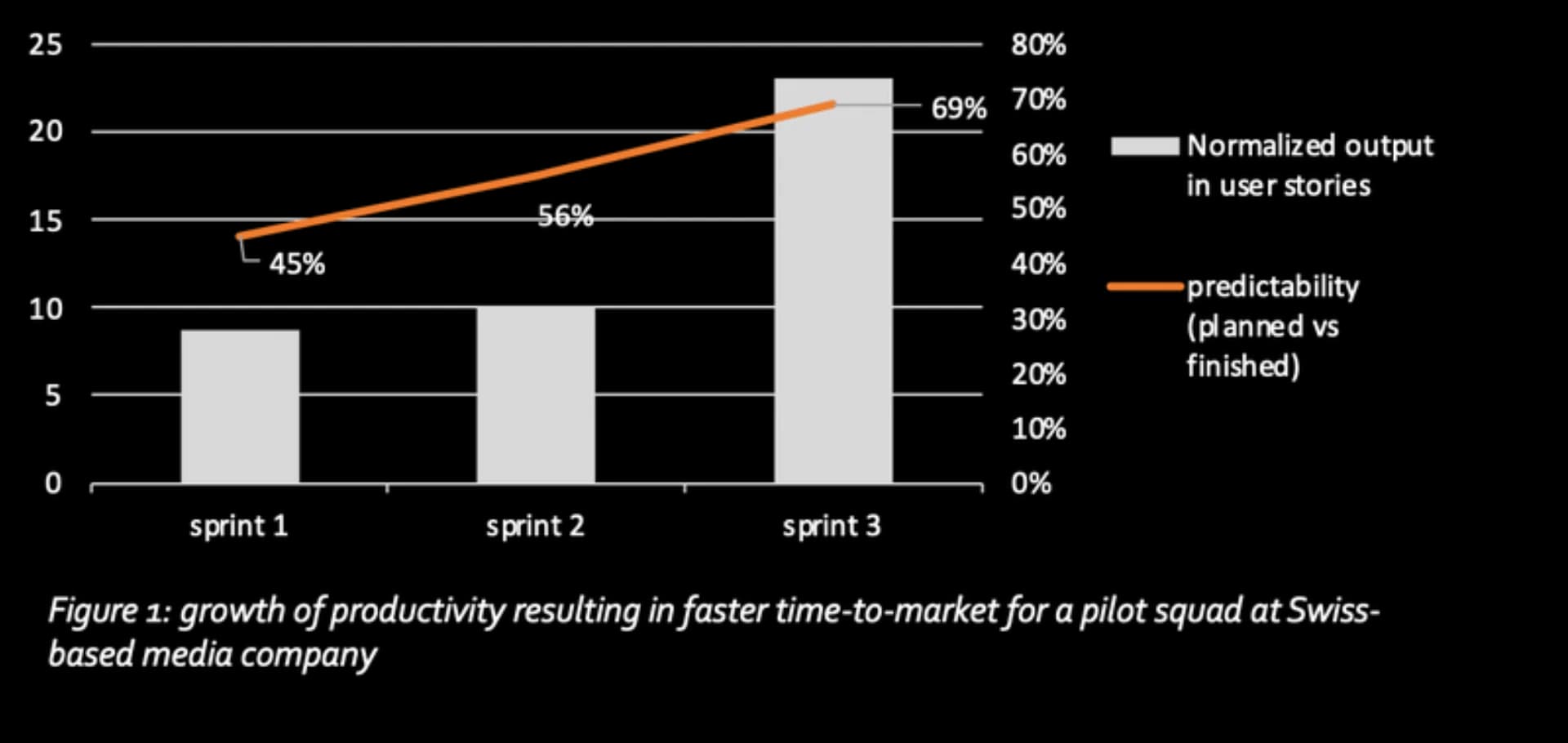

True speed requires the whole organization to think and act differently. A Swiss-based media company realized it had no shortage of ideas, but only a fraction made it to implementation and even these happy few suffered from long lead times. Rethinking the collaboration structure and process lead to cross- functional teams of nine people, combining profiles from marketing, communication, web development and more. Within 3 months project delivery (a campaign, a promotional article, a landing page) went up significantly as below graph shows.

Play 2: Decision making agility

Market circumstances change. Multiplied by the number of markets served globally, adding an equal number of regulatory bodies and you get a sense of the problem faced by global pharmaceuticals. No amount of development capacity operating at maximum conceivable speed will ever be able to satisfy all affiliate needs all the time all at once. Enter the challenge of prioritization for global capabilities. Many multinationals that have grown from a central hub (e.g. airlines), have followed a productization strategy. Product [Management / Marketing / Strategy] has the authority and capabilities to make reasoned decisions in relative isolation.

In pharma companies, due to the nature of their products and market segments they serve, local knowledge is vital for the success of any new product or campaign launch. And that only supports the decentralized nature pharma companies already enjoy due to a history of acquisitions. And as we know, the dynamics in large, decentralized conglomerates is very different. As a result, decision making is a far more delicate matter.

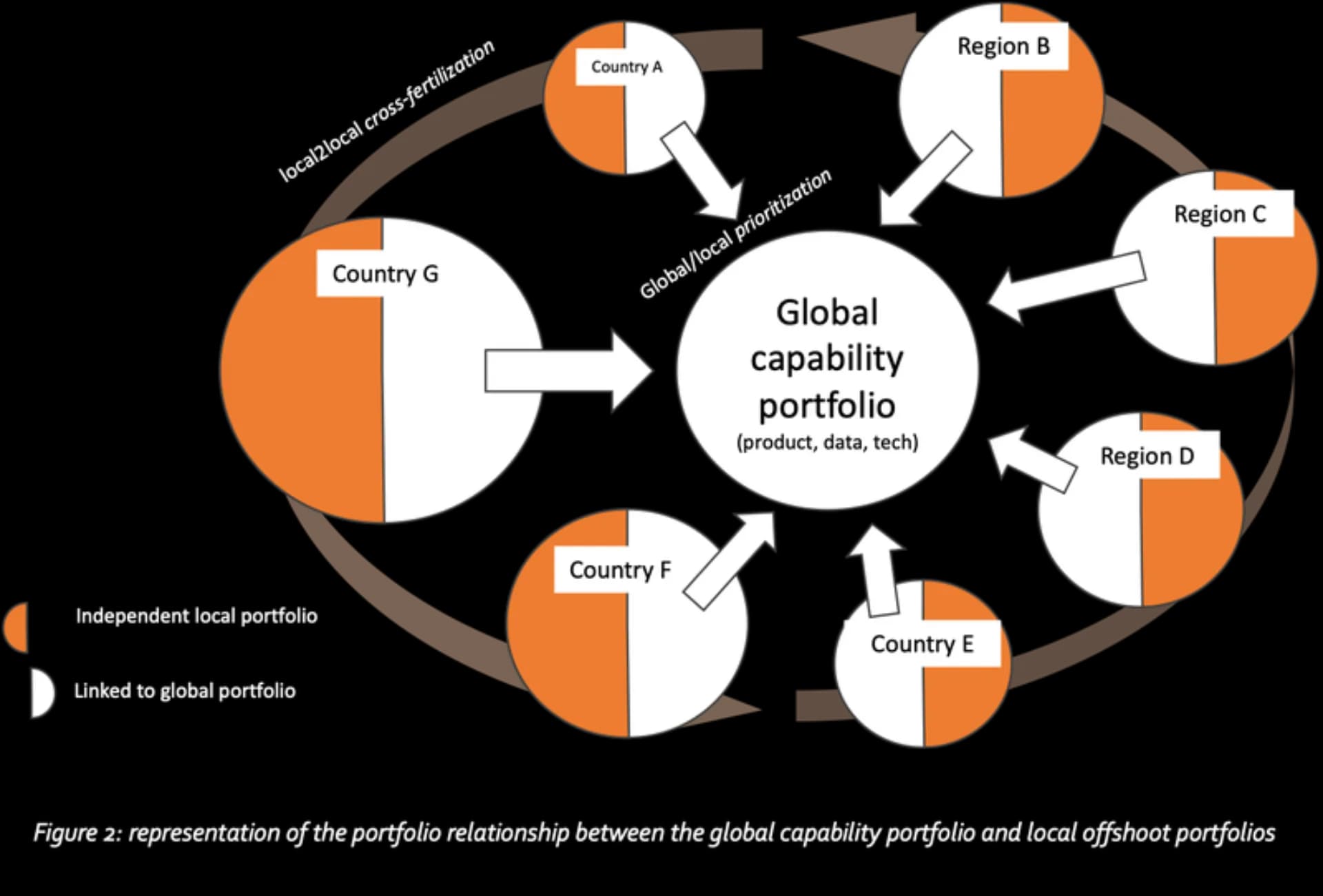

Again, pharma can take lessons from other conglomerates. Take a French-based multinational as an example. With 9 acquisitions in the last 5 years to a total of 20 in its history, it faces similar challenges of product-, data- and technology-portfolio alignment. They recently realized their project-portfolio governance did little to create a realistic and holistic view of priorities, “prioritization spaghetti would be the more accurate description.” Their journey now emphasizes transparency at the global portfolio level and continuous prioritization over smaller pieces – Minimum Viable Products - of the initiative roadmap (smaller ‘bets’). It will allow them to shorten the feedback loop to all regional participants, earn their trust and remain agile. Amplifying this agile portfolio governance for global capabilities is the emergence of local portfolio governance offshoots. Supported by a central team of experts, local and regional offices are adopting the same decision-making framework. From a local perspective, this strengthens their argumentation to the global team. But it also allows them to safely separate initiatives that do not need global support from the ones that do creating a 2-track portfolio at the local or region level.

The role of the global team does not need to stop there. A parallel can be made with B2B tech companies. A European technology provider has a dominant position in travel tech, counting many of the major airlines as their customers. To serve their customers they rely for a large part on central product teams. But from a customers’ point of view, this is only a part of their total development capacity.

Often, they have their own teams that need to integrate with the company’s products. They are not only interested in prioritizing all different customer requests for their own backlog in a manner that is explainable. They also promote and facilitate in-depth knowledge sharing across their customer base on topics that does not directly concern them yet. They know that such conversations will lead to more uniform airline technology roadmaps which supports the reuse of their capabilities. Providing such a knowledge platform also makes them aware of what is happening, and where future global demand will be. Though different in context, similar principles in dynamics apply to global and regional teams in decentralized organizations.

Play 3: Outcome-based goal alignment

A well-functioning portfolio management system allows for relatively quick comparison of a set of initiatives against a known set of value indicators. But that presumes we all have the same goal in mind. Which for large organization is rarely the case. To really reap the benefits of a central resource hub unhindered by the inherent increase in decision-making complexity plays 1 and 2 need to be accompanied by play 3.

A German tech conglomerate builds, markets and sells amongst others energy grid software globally. For all organizational functions and sites to work together and prioritize ideas effectively, they make sure each of them has the same set of objectives in mind. Top-level objectives are shared and form the basis for department goals. Key results – a system of outcome-oriented measurements – provide the necessary clarity and focus: without these strategies often risk becoming a container for everything, hollow words, or both. Conversations around these OKRs ensure high-level alignment and allow management teams to examine the inherent trade-offs between them. As such they also serve as a cheap litmus test: little acceptance signals the organization hasn’t bought into such plans just yet. Regular review cycles – typically the quarter – between leadership ensures also these objectives move along with reality. With an outcome-based objectives mechanism in place, global functions can always bring tense conversations back to the impact initiatives have on them. And working from a shared context is also the best guarantee that the discussions you do have, are really the ones in pursuit of selecting the best ideas to fit a shared agenda. The global functions in pharma companies can benefit a lot from this level of alignment with their affiliates.

Making an impact in your organization

In the decentralized organizational setup common among pharma companies, strongly centralized change programs are highly scrutinized. The prevailing thought appears to be that the benefits of decentralization (local accountability, customization to context) also apply to organizational change. We would argue this to be a fallacy in the highly connected areas of technology-supported business functions. Yes, adaptation to local context is necessary. But where alignment between organizations is expected, working from common principles, a common heartbeat and a common language is a must.

Second, bottom-up changes in the way of working, however promising, just don’t scale to its full potential without strong leadership support. Such support goes beyond sponsorship. In all the cases mentioned in this article specific leaders have actively encouraged their units, argued with their peers, and convinced their superiors to offer the means as well as the freedom to experiment. They managed to build a coalition and sought the necessary expertise internal and external.

A Dutch public transport organization sought to radically transform their organization, merging Commercial with IT for all related business functions. A complex transformation breaking through silos and hierarchy, the transformation itself is set up as a program. The Director Commercial and IT was directly responsible for the success of the transformation. The program worked with a smaller dedicated transformation team augmented with part- time change leads and ambassadors spread out over the Commercial and IT organizations functions. In this way, they kept track of the success of – and lessons learned from – the transformation to cross-functional teams in all areas whilst giving them autonomy to fit the changes to purpose as needed.

The described transformation approach is tested through and through at many other clients like Air France -KLM, Amadeus IT Group, and high-tech giant ASML. It is based on the same principles that allow agility at scale: learning in rapid cycles and continuous improvement.

Related insights