A fair comparison: measuring pay equity

At first glance, measuring the gender pay gap seems straightforward – just compare the average salaries of men versus women, right? Well, not quite. The reality is far more nuanced and often up for debate. Factors like part-time work and job levels skew these averages, potentially masking underlying issues of inequality. To answer the question: are we paying our employees equally for the same work, an organization must calculate the corrected pay gap. A more comprehensive metric that factors in variables such as job level and experience to reveal the true state of pay equity within an organization. It's not just about identifying a gap but understanding why it exists and what actions can rectify it. Highberg's approach to calculating equal pay for equal work sheds light on the complexities of pay disparity and paves the way for meaningful change.

Key Insights

- A first step for any organization is calculating the nominal pay gap

- For organizations with over 500 employees, it is also possible to calculate the corrected pay gap

- Before it is possible to calculate whether there is equal pay for equal work in an organization, it is necessary to determine what is meant by 'pay', what factors determine 'equal work', and which employees will be included in the analysis

- As a result of these choices, the corrected pay gap can be calculated. This involves correcting the nominal pay gap based on explanatory variables such as job level, experience, performance, etc

How did Highberg get started with equal pay research?

In 2018, Highberg, formerly known as AnalitiQs, conducted the first equal pay analysis for Aegon, in accordance with a collective bargaining agreement. Gido van Puijenbroek, who was interim responsible for People Analytics and HR Technology at Aegon at the time, led this initiative. Previously, such analyses were mainly carried out by the Dutch Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) or academics at the sector level. In the United Kingdom, examining pay gaps was already more common, but the methods used were simpler and legally prescribed. In Aegon's case, however, it was an individual company which required careful consideration when selecting relevant data. Highberg aimed for a more in-depth analysis than was customary at the time, looking not only at the nominal difference but also at the corrected difference. This approach provided the opportunity to explain potential pay gaps, allowing Aegon to respond more effectively to the results.

From a nominal to a corrected pay gap analysis

There are two ways to examine a pay gap, based on the difference between the nominal and corrected pay gap. A previous article discusses this in detail. In a nominal pay gap analysis, descriptive statistics are used to calculate the gender pay gap for the entire organization and for subgroups, such as per job scale, age category, or type of work. This analysis provides insights that comply with legislation, such as CSRD, UK pay legislation, and the EU Directive Pay Transparency.

However, a nominal pay gap analysis cannot fully explain why pay gaps occur and if these can be explained by numerous variables (such as job scale, experience, performance, etc). This is possible with a corrected pay gap analysis. Such an in-depth analysis is possible for organizations with more than 500 employees, to make sure that there are enough employees for representative subgroups.

Determining what is pay

To conduct a pay gap analysis, nominal or corrected, it has to be determined which data should be included in the research. In doing so, we first look at which elements of pay should be included as part of the total pay in the analysis. Of course, monthly base pay should be included, as well as holiday allowances or a personal budget. In addition, employees often receive variable remuneration, such as bonuses, gratifications, and allowances for their specific work. Moreover, things like the number of vacation days or pension rights should be taken into account, specifically when these are not the same for all employees. The elements that should be included in the analysis vary per organization.

To ensure a fair comparison of salaries, the salary data for all employees is converted into full-time salaries. This can be done either on an annual basis or a monthly basis. The same applies to variable salary, which is calculated uniformly for all employees.

For legislative purposes, only analyzing base pay is not enough. The corporate social responsibility directive (CSRD) requires an organization to include total remuneration, and the EU Directive Pay Transparency asks to split between base and variable pay.

Some salary components are more difficult to calculate than others. For example, mobility allowances are excluded in many analyses, as it is difficult to calculate the monetary equivalent of a lease car or travel card. However, Highberg urges organizations to gain insight into these numbers as these can impact the nominal and corrected pay gap.

Defining equal work

For organizations to answer the question: are we paying our employees equally for the same work or work of equal value (as the EU Directive describes it), it is important to define what is meant by 'equal work.' In practice, only comparing employees who do the exact same work or have the same function title is impossible, as in most cases groups are not big enough for equal comparison.

Most organizations use job scales to define equal work. This might include a broad set of different jobs, but as most job scales are developed based on a Hay-score or similar job evaluation system, it gives an idea of jobs with the same level of responsibilities. Calculating a nominal pay gap per job scale (or organization equivalent) is a good start to indicate a potential pay issue.

However, only calculating the nominal pay gap per job scale might not provide enough insights. For example, this approach does not take time in job scale or performance into account, which might be relevant factors to explain a remaining gap. Therefore, it is useful to also calculate the corrected pay gap. This includes adding variables such as experience. These variables provide insight into employees' personal and professional development and often form the basis for remuneration structures. In addition, specific industry or organization-related variables can be important for determining "equal work". This could include specific requirements, skills, or certifications that are unique to a particular industry.

Who will be included in the study?

Finally, it might be challenging to define what employees to include in the analysis. There can be several reasons why certain groups of people are not included in an equal pay analysis. For example, freelancers, external consultants, interns, or contingent workers may not be included in an equal pay analysis, because their salaries and allowances are often determined on a different basis than 'internal’ employees.

In addition, specific positions or roles may be excluded if they differ significantly in responsibilities, required skills, or experience. Certain positions may have a unique pay structure that is not directly comparable to other positions within the same organization. Some companies also exclude senior management positions, such as the board, due to the variability in compensation structures, such as bonuses and performance-related compensation. These remuneration structures are not always directly comparable to those of employees who are not part of the management. However, an organization must include all internal employees in their analysis to be compliant.

How is equal pay then calculated?

Once the factors involved in the study are identified, the analysis can be conducted. This analysis is what makes Highberg unique. Most organizations typically use regression for analysis, but this method has a larger margin of error, which means that compensation differences cannot be fully explained. The method used by Highberg does not have this issue.

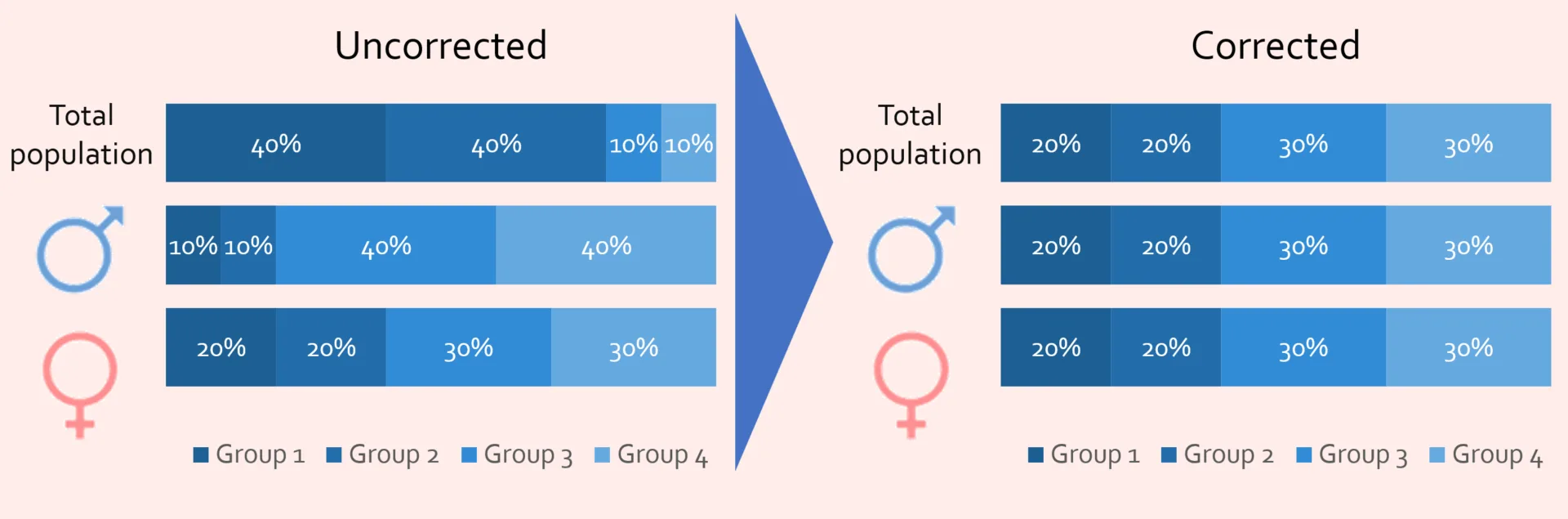

In this method, the population is first weighted, so the distribution of background variables is equal. As an example, we can take gender. We aim to have an equal number of men and women in each group. See the image below for illustration.

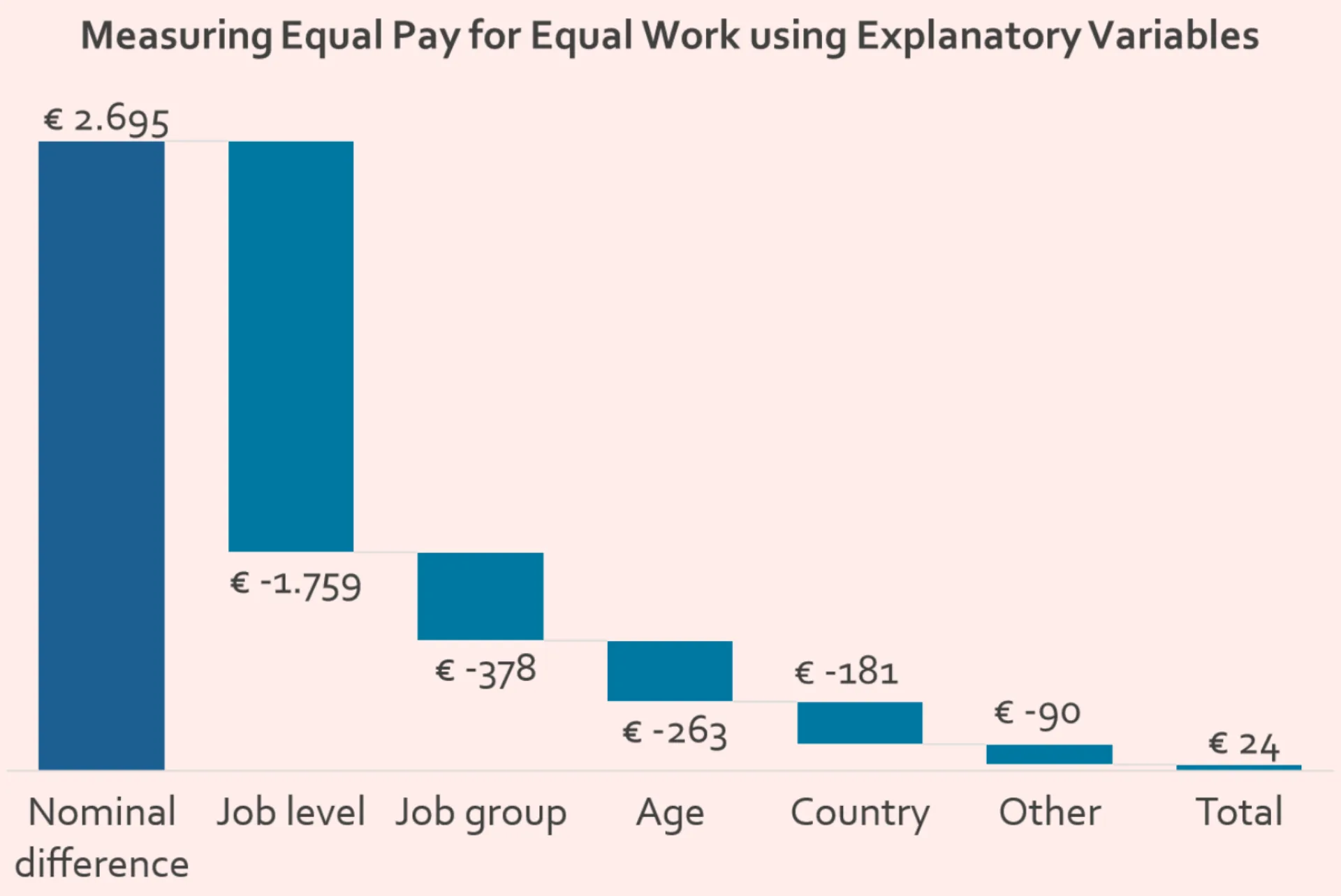

Then, an analysis is conducted to calculate the influence of background variables on total compensation. This influence serves as the basis for the adjusted compensation difference. The attached image shows to what extent background variables can explain the nominal pay gap. The nominal difference, in this case, the amount that men earn more than women, is 2,695 euros. However, 1,759 euros can already be explained by job level: in this example, men are more likely to be in higher positions than women. When adjusted for the other variables, in this case, job group, age, country, and other variables, the corrected pay gap is equal to 24 euros, meaning that men earn 24 euros per year more for the same work, which is nearly zero per cent difference of total compensation. Thus, this figure clearly shows why the adjusted pay gap is a better measure of pay equity.

Next steps

Highberg recommends starting with a study into pay equity to tackle possible pay gaps in an organization. Contact Henrieke van Bommel to get started right away or find more information about Highberg's services.

Related insights